Referring to it as the Scots Dyke, some showed it joining with the Catrail over the Scottish border and extending south to the border with County Durham south-east of Allenheads. Some even had it extending to South Yorkshire! These days, Scots' Dyke refers to a boundary earthwork constructed in the C16th to fix part of the border between Scotland and England, in the area of the West Marches.

The Black Dyke has been claimed as a fortification, a boundary, a military way, a prehistoric road, a drove for cattle, and even as a cattle grazing barrier. Similar to the Catrail, though, was it ever substantial enough to be an effective military barrier, and is more likely to have been a territorial boundary marker, possibly dating from the early Middle Ages but possibly even prehistoric.

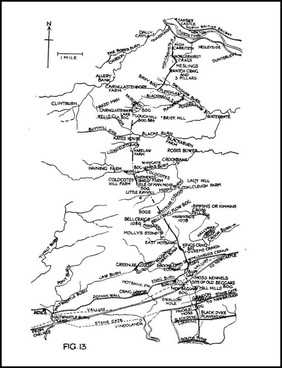

A well-known portion of the work extends northwards from the South Tyne between Bardon Mill and Haydon Bridge, to the southern margin of Grindon Lough, and this very visible feature of the landscape attracted the early interest of the C18th antiquaries. Unfortunately, some of the best proportions of its length to the north of Hadrian's Wall are now obscured by the extensive Wark Forest plantations.

In the Middle Ages, a considerable stretch of the Black Dyke acted as part of the boundary of the Manor of Wark-on-Tyne and, as shown in the above photo, long lengths are still utilized as modern boundaries between farms, townships and parishes.

Its line to the north disappears in the vicinity of the Roman vallum and may here have coincided with that of Hadrian's Wall. Because its line is not clear in the region of the Wall, Spain postulated that it must predate the Roman era. It reappears just west of, and below, Sewingshields Crags where Spain records the ditch as six foot deep. From here it heads north, towards the summit of Queen's Crags. A three mile stretch of the Black Dyke forms the boundary between the farms of Hotbank and Sewingshields, and is also part of the Parish boundary between Haltwhistle and Simonburn.

Queen's Crags is the site of a Roman Quarry, where wedge marks can still be found in the process of splitting one large boulder. A Roman inscription of four lines was found below an overhang here in 1960.

There is also the usual legend in these parts that King Arthur and his court rest asleep beneath the walls of Sewingshields Castle, which used to stand about a mile to the east, awaiting call by horn when they are again needed.

George Spain proposes a defensive line from western invaders, even possibly the Romans, for both the Black Dyke and Catrail earthworks. Modern thought would make this proposal less likely but when they were made and for what purpose still remain unknown.

Keys to the Past local history description of Wark states:

An Iron Age tribal boundary may have survived in the form of the Black Dyke. Although it is not a continuous ditch and rampart, the ditch lies on the west as if to anticipate an attack from this direction, it runs for several kilometres from the North Tyne to the South Tyne through the parish of Wark; the monument is debatable and little known.

- The earthwork can be recognised as a bank of variable width and height with a prominent ditch on its west side. However, other ancient boundaries in parts of this landscape are today just as impressive and the Black Dyke fails to impress in many parts of its route.

- The Black Dyke is often coincident with modern boundaries between farms and parishes.

- In places though it is not followed by existing boundaries and has a course which is curved or on a different alignment. For example, from Muckle Moss heading south, the Black Dyke enters Blackdyke Plantation at a narrow angle and runs within the plantation to emerge from it again back near the boundary on the Haresby Road.

- The Black Dyke can be intermittent in having breaks at natural features (such as Muckle Moss and Grindon Lough) which themselves would be sufficient to hinder crossing and act as natural boundaries. Perhaps the continuation of the dyke was marked across the bog using other means (fence or posts).

- South of Haresby Road, heading downhill, the Black Dyke is a prominent landscape feature although its line may have been preserved by the modern boundary wall which was built on top of its bank.

- Where the wall bends sharply to the west (opposite Haresby), both the ditch and mound of the Black Dyke end completely. Spain considered that it had been ploughed out where it crossed the field but the complete loss of its line suggests to me that it didn't follow his projected course. An alternative suggestion is that the Black Dyke ditch joined the Whitechapel Burn which comes close to the wall at this point. Further down (in trees), the burn swings sharply to the west in a steep sided valley, and eventually joins the River Tyne directly opposite its confluence with the River Allen. The parish boundary still follows this prominent natural feature.

- There is a low bank running parallel to the modern wall on Spain's projected route of the Black Dyke south over Whitechapel Hill, but the lack of a ditch on the west side of this feature does not fit with the earthwork, and there is certainly no trace of it south of the hill.

- This new line I propose makes possible an extension of the boundary south of the River Tyne, as proposed by some earlier writers, using the natural line south made by the River Allen. This would explain the fact that no trace of the dyke was found by Spain on the south bank of the Tyne, east of the Allen.

- Tracing the line of the dyke north from Sewingshields Crags to Bellcraig Flow and onward, where it was possible, into the depths of the great Wark Forest west of Stonehaugh, I gradually lost enthusiasm for the Black Dyke being any kind of important boundary.

The situation south of Howlerhirst Crags, around Watch Crags and Watson's Walls, doesn't look quite as clear cut though. I'll let you know when I have made the visit.

George Spain in 1922 wrote the following description in his account of the Black Dyke:

The view to the south-west from the top of Watch Crag across the Pundershaw basin is a fine one. Harelaw, with its little farm perched on the hill top, is a conspicuous feature and the dark green ribbon of the ditch of the Black Dyke leaves the base of the three pillars and winds in a graceful curve for a mile across the moorland into the middle distance of the Pundershaw slopes.

It appears no different to the remains of a large number of old boundaries, of indeterminate age, that previously divided up these moorlands, and some are much better defined. Its curving line and approach to the centre of Watch Crags are interesting features though.

After a short gap at a bog north-west of Watch Crags, Spain picks up its line again on the route of the current parish boundary between Bellingham and Falstone. He describes a stone wall, built on the Dyke's 2 to 3 foot high mound, running north for nearly half a mile, accompanied by a ditch between 10 to 12 feet wide on its west side.

Higher towards the west, Howlerhirst Crags form a largely uncrossable natural west to east barrier and Spain favours this line for the Black Dyke. It leads naturally towards the deep valley of the High Carriteth Burn which heads north to join the River North Tyne. The crags are still used today as a boundary (occassionally augmented by a fence) and a continuing prominent line followed by a modern fence extending from the north-west side of the hill down to the burn.

I seem to remember being fairly sceptical above of the extent of this dyke across the wider landscape which was suggested by George Spain.

Something I read recently seems to agree with my view:

Archaeology in the North. Report of the Northern Archaeological Survey By Northern Archaeological Survey, P. A. G. Clack, P. F. Gosling, Eds. (1976).

Section IX. A Survey of Wark Forest by Revd. T Hayes states (p.248):

"Whether the latter is a single continuous feature extending northwards from the Wall and cutting the corner of our area is questionable."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed