The canons of Blanchland, on obtaining this grant of Heddon Church, appear to have immediately commenced building the present chancel. It was usual for monastic foundations to rebuild or improve churches given them, and thus please villagers only too glad, probably, to escape from the deadening monotony of the parochial system, even at the cost of seeing their great tithes appropriated to a distant abbey. For some reason the great tithes of the township of West Heddon were reserved to the vicar of Heddon-on-the-Wall, who is consequently rector of West Heddon.

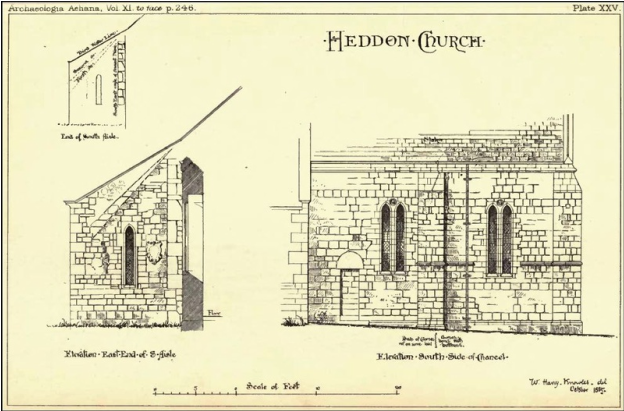

If anything be left of the Church of St. Andrew before 1165 it is the quoin of rough stones (see Plate XXV.), the alternate ones placed about two feet on end, that is seen built for eighteen inches from the chancel into the east wall of the south aisle. This apparent piece of 'long-and-short' work may be the east end of the south wall of a very

early nave.

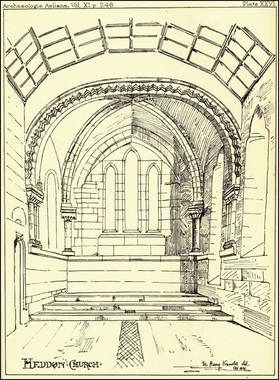

The Norman chancel (see Plate XXVI.) is divided inside into two portions by a fine zigzag arch, peculiar in construction and still more peculiar in position. The double row of teeth forming this zigzag are not, as in most instances, arranged perpendicularly, but stick out horizontally as if in the wide-open mouth of some monster. A row of similar half-teeth are worked in below the roll-band, which, with the moulding above, completes the arch. Two zigzag lines incised in what carrying out the comparison forms the jaw beneath the lower set of fangs, considerably heighten the effect. [29]

From some cause that is not apparent [30] this arch has been so depressed as to acquire a flat appearance in the centre; indeed, a small keystone seems to have been inserted. The springers of the upper part of the arch are, especially on the south side (which has a nick cut in it to show a little more of the zigzag), entirely hidden by the walls of the western portion of the chancel, which are decidedly Norman, though possibly not of the same date as those of the vaulted compartment to the east of the arch. The flat springers of the arch stand on either side 4 inches further in than the springers of the double ribs that support this vault. On the north side, the flat springer of the arch is 6 inches high, that of the double rib 8 inches; on the side the proportions are reversed, being 7 and 51/2 inches respectively. The walls of the chancel lean over considerably to the outside. [31] Outside, this zigzag arch is supported by two characteristic Norman buttresses, without set-offs, that finish with a rough slope to a string-course just below the parapet. At about 8 feet from the ground these buttresses are crossed by the semi-hexagonal string-course that runs round the walls and corner buttresses of the east portion of the chancel, but is not continued round the west portion.

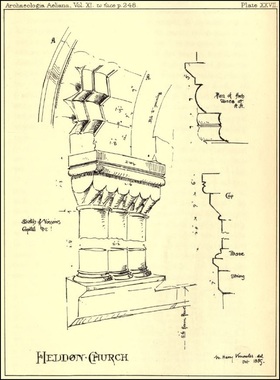

A string-course runs round also the interior of the east portion; slabs are laid at its north-east and south-east angles to carry single pilasters set corner-wise on, from which the double ribs of the vault spring, intersecting each other, over to the eastern of the triple semi-columns, set on similar slabs, but in the line of the walls, the two western of which, on either side, support the zigzag arch. These pilasters have all flat-faced capitals, with escalloped or invected edges. The north cluster differs from the west in having what look like small stems between the escalloping (see Plate XXVII). The bases of the two single pilasters and of the two clusters are all different. The base-mouldings of the clusters are carried an inch or two further along the wall to the east and west.

One of the original little round-headed Norman windows, a mere 6-inch slit, 3 feet long, nobly splayed on the inside, is preserved in the north wall, near the altar. Outside, three holes have been punctured in the stone above it, perhaps for a grating. Probably there was a similar window in the east wall. [32] The eastern angles of the chancel are overlapped by Norman buttresses like those already described.

In the eastern portion of the chancel there is, in the south wall, a doorway with a plain tympanum that looks almost earlier than Norman; and in the north wall, above the present vestry door, is a semicircular doorhead in a single stone, which also bears a very archaic character. This doorhead seems now at a great height from the ground, but the bases of the chancel arch prove the chancel floor to have been originally about eight inches above the present level. In breaking the arch for the organ-chamber through the wall to the west of this doorhead, part of the splay of a Norman window was found beneath the plaster, covered with the red and black frescoing that appears to have been general throughout the church, and is especially to be noticed on the simple Norman font.

It is very dry work minutely describing a building of considerable complexity that is not before the eyes of an audience. Those who take an interest in the architectural puzzles connected with Heddon Church may again visit it when summer comes round, and perhaps deign to put these notes in their wallet. My own theory thrown out

without dogmatism is that the canons of Blanchland found the Church of St. Andrew at Heddon consisting simply of an ancient nave with, probably, an apse at the east end. Intending to build an entirely new church they began the vaulted compartment over the present altar to the east of the apse, in order to have this ready for the celebration of

mass33 before pulling down the old nave. The zigzag arch was to have been the chancel arch of their new church. But when this sanctuary was finished the canons changed their minds, from motives of economy, and joined it on as best they could to the old nave, destroying the apse in the process. [34]

If anything be left of the Church of St. Andrew before 1165 it is the quoin of rough stones (see Plate XXV.), the alternate ones placed about two feet on end, that is seen built for eighteen inches from the chancel into the east wall of the south aisle. This apparent piece of 'long-and-short' work may be the east end of the south wall of a very

early nave.

The Norman chancel (see Plate XXVI.) is divided inside into two portions by a fine zigzag arch, peculiar in construction and still more peculiar in position. The double row of teeth forming this zigzag are not, as in most instances, arranged perpendicularly, but stick out horizontally as if in the wide-open mouth of some monster. A row of similar half-teeth are worked in below the roll-band, which, with the moulding above, completes the arch. Two zigzag lines incised in what carrying out the comparison forms the jaw beneath the lower set of fangs, considerably heighten the effect. [29]

From some cause that is not apparent [30] this arch has been so depressed as to acquire a flat appearance in the centre; indeed, a small keystone seems to have been inserted. The springers of the upper part of the arch are, especially on the south side (which has a nick cut in it to show a little more of the zigzag), entirely hidden by the walls of the western portion of the chancel, which are decidedly Norman, though possibly not of the same date as those of the vaulted compartment to the east of the arch. The flat springers of the arch stand on either side 4 inches further in than the springers of the double ribs that support this vault. On the north side, the flat springer of the arch is 6 inches high, that of the double rib 8 inches; on the side the proportions are reversed, being 7 and 51/2 inches respectively. The walls of the chancel lean over considerably to the outside. [31] Outside, this zigzag arch is supported by two characteristic Norman buttresses, without set-offs, that finish with a rough slope to a string-course just below the parapet. At about 8 feet from the ground these buttresses are crossed by the semi-hexagonal string-course that runs round the walls and corner buttresses of the east portion of the chancel, but is not continued round the west portion.

A string-course runs round also the interior of the east portion; slabs are laid at its north-east and south-east angles to carry single pilasters set corner-wise on, from which the double ribs of the vault spring, intersecting each other, over to the eastern of the triple semi-columns, set on similar slabs, but in the line of the walls, the two western of which, on either side, support the zigzag arch. These pilasters have all flat-faced capitals, with escalloped or invected edges. The north cluster differs from the west in having what look like small stems between the escalloping (see Plate XXVII). The bases of the two single pilasters and of the two clusters are all different. The base-mouldings of the clusters are carried an inch or two further along the wall to the east and west.

One of the original little round-headed Norman windows, a mere 6-inch slit, 3 feet long, nobly splayed on the inside, is preserved in the north wall, near the altar. Outside, three holes have been punctured in the stone above it, perhaps for a grating. Probably there was a similar window in the east wall. [32] The eastern angles of the chancel are overlapped by Norman buttresses like those already described.

In the eastern portion of the chancel there is, in the south wall, a doorway with a plain tympanum that looks almost earlier than Norman; and in the north wall, above the present vestry door, is a semicircular doorhead in a single stone, which also bears a very archaic character. This doorhead seems now at a great height from the ground, but the bases of the chancel arch prove the chancel floor to have been originally about eight inches above the present level. In breaking the arch for the organ-chamber through the wall to the west of this doorhead, part of the splay of a Norman window was found beneath the plaster, covered with the red and black frescoing that appears to have been general throughout the church, and is especially to be noticed on the simple Norman font.

It is very dry work minutely describing a building of considerable complexity that is not before the eyes of an audience. Those who take an interest in the architectural puzzles connected with Heddon Church may again visit it when summer comes round, and perhaps deign to put these notes in their wallet. My own theory thrown out

without dogmatism is that the canons of Blanchland found the Church of St. Andrew at Heddon consisting simply of an ancient nave with, probably, an apse at the east end. Intending to build an entirely new church they began the vaulted compartment over the present altar to the east of the apse, in order to have this ready for the celebration of

mass33 before pulling down the old nave. The zigzag arch was to have been the chancel arch of their new church. But when this sanctuary was finished the canons changed their minds, from motives of economy, and joined it on as best they could to the old nave, destroying the apse in the process. [34]

29 Other examples of zigzag arches treated in this horizontal fashion are to be seen at Norham and Jedburgh; but the finest of all are perhaps those at St. Peter's, Northampton, and in the Great Hall of Rochester Castle.

30 It has been suggested that this depression may have been caused by the superincumbent weight of the east wall of a central tower between this arch and the nave. The abandonment of this project, or the fall of the tower, would account for the slightly later date of the west portion of the chancel.

31 The enormous number of interments in this chancel may have caused the foundations to slide in. More than a thousand persons have probably been buried inside the church.

32 "Mrs Jane Cowling, formerly of Richmond, widdow, was interred in the Quire under ye easter Little Window. Jan. ye 25th 1707/8." (Heddon Register.) The easier little Window probably means the original Norman east window,

which seems to have been taken out at the 'restoration,' about 1840, when a plain three-light window with the Bewicke arms and the letters M. B. in coloured glass was inserted, to be removed in 1873. Mrs. Jane Cowling was the mother-in-law of the Rev. Miles Birkett, vicar 1693-1709. Her interment under, or just behind, the communion-table appears now revolting and irreverent ; but then it was quite in the ordinary course, for we read also that ' Mary, dau. to James Carmichael, vicar, was buried in the church nigh the south end of the communion-table, Sept. the 9th, 1712'; her sister, Eleanor, on 26th April, 1721, 'nigh the south wall just below the steps'; while their father and mother were both buried in the chancel, ' within the rails.'

33 In the autumn of 1884 I noticed at Linz, on the Danube, a good example, in the new cathedral building there, of this anxiety to finish the east end of a church first, especially for the services of the Latin ritual.

34 Mr. C. C. Hodges, I am glad to say, concurs in this view. On the other hand, the Rev. J. R. Boyle, who, in company with Mr. W. H. Knowles (see Appendix A), has spared no pains in studying Heddon Church, refuses to recognize the quoins at the juncture of the chancel and south aisle as ' long-and-short' work, but refers them to the same Transitional epoch as the semi-Norman bays of the north aisle. On the question of fact as to the character of the quoins, we are completely at variance ; and I submit that Mr. Boyle's theory fails to explain how it was that the zigzag arch did not become the chancel one.

30 It has been suggested that this depression may have been caused by the superincumbent weight of the east wall of a central tower between this arch and the nave. The abandonment of this project, or the fall of the tower, would account for the slightly later date of the west portion of the chancel.

31 The enormous number of interments in this chancel may have caused the foundations to slide in. More than a thousand persons have probably been buried inside the church.

32 "Mrs Jane Cowling, formerly of Richmond, widdow, was interred in the Quire under ye easter Little Window. Jan. ye 25th 1707/8." (Heddon Register.) The easier little Window probably means the original Norman east window,

which seems to have been taken out at the 'restoration,' about 1840, when a plain three-light window with the Bewicke arms and the letters M. B. in coloured glass was inserted, to be removed in 1873. Mrs. Jane Cowling was the mother-in-law of the Rev. Miles Birkett, vicar 1693-1709. Her interment under, or just behind, the communion-table appears now revolting and irreverent ; but then it was quite in the ordinary course, for we read also that ' Mary, dau. to James Carmichael, vicar, was buried in the church nigh the south end of the communion-table, Sept. the 9th, 1712'; her sister, Eleanor, on 26th April, 1721, 'nigh the south wall just below the steps'; while their father and mother were both buried in the chancel, ' within the rails.'

33 In the autumn of 1884 I noticed at Linz, on the Danube, a good example, in the new cathedral building there, of this anxiety to finish the east end of a church first, especially for the services of the Latin ritual.

34 Mr. C. C. Hodges, I am glad to say, concurs in this view. On the other hand, the Rev. J. R. Boyle, who, in company with Mr. W. H. Knowles (see Appendix A), has spared no pains in studying Heddon Church, refuses to recognize the quoins at the juncture of the chancel and south aisle as ' long-and-short' work, but refers them to the same Transitional epoch as the semi-Norman bays of the north aisle. On the question of fact as to the character of the quoins, we are completely at variance ; and I submit that Mr. Boyle's theory fails to explain how it was that the zigzag arch did not become the chancel one.

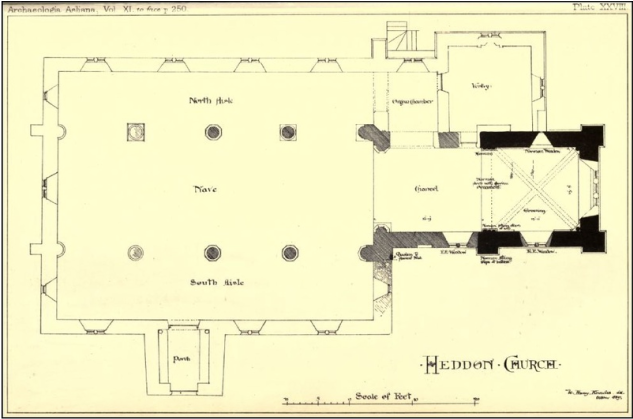

The history of the rest of the church is comparatively plain sailing. Probably before the close of the twelfth century the two eastern bays of the north aisle were thrown out. These are very noble examples of Transition work. The semi-column at the chancel corner, and the column west of it have elaborate Norman capitals; the massive arches they support are pointed. At successive periods during the thirteenth century the two double-lancet windows in the south wall of the chancel (with curious faces that in the east one crowned between the tops of their lights) were inserted; another bay, with a round column of much the same character but considerably higher than

the Transition ones and a wide soaring arch, was added to the north aisle; the present chancel arch (the semi-octagonal shafts of which rise from different levels, the north one having the more elaborate capital with nail-head mouldings, the south one the more elaborate base) was erected; and the south aisle built. The pillars of the south aisle have octagonal capitals, the arches internal ribs; the moulding over the arches does not come down to the capitals as it does over those of the north aisle.

The roof over the nave, and the two aisles, came originally down in one long straight pitch that has left its mark on the east wall of the south aisle (see Plate XXV). This was very usual at that time, but the walls of the aisles must, in consequence, have been very low, and the windows in them wretchedly small. Probably there was a sort of gable for additional height above the principal door of the church which opened into the westernmost bay of the south aisle. The square capitals of the detached shafts on each side of this door that support a bold architrave with

a hood moulding over it, are buried in the rough acute-arched vaulting of the porch, an addition probably of the fourteenth century. The bases of these shafts are hidden by stone seats. The walls of the aisles were probably raised when the porch was built, and roofed to a pitch flatter than that of the nave, though not so flat as their present pitch, as may also be seen on the east wall of the south aisle. About 1840 the gallery which had been erected at the west end of the church was taken down, and, as a substitute, the nave was lengthened and an extra

bay added to each aisle, at the same time, probably, a clean sweep was made of all the old monuments, &c. An octagonal vestry was built out at the west end of the nave, in place of one under the gallery which was pulled down. This eccentric vestry was, in its turn, demolished about 1870, and one in no better taste added on the north of the

chancel, destroying its external features. In 1873, the church was conscientiously repaired, and an organ chamber inserted between the new vestry and the north aisle.

The first vicar of Heddon whose surname we know is John de Darlington, who exchanged the living for that of Kirkharle in 1350.

The following list [35] gives, as far as has been ascertained, the dates when his successors were appointed, and whether they resigned or died :

the Transition ones and a wide soaring arch, was added to the north aisle; the present chancel arch (the semi-octagonal shafts of which rise from different levels, the north one having the more elaborate capital with nail-head mouldings, the south one the more elaborate base) was erected; and the south aisle built. The pillars of the south aisle have octagonal capitals, the arches internal ribs; the moulding over the arches does not come down to the capitals as it does over those of the north aisle.

The roof over the nave, and the two aisles, came originally down in one long straight pitch that has left its mark on the east wall of the south aisle (see Plate XXV). This was very usual at that time, but the walls of the aisles must, in consequence, have been very low, and the windows in them wretchedly small. Probably there was a sort of gable for additional height above the principal door of the church which opened into the westernmost bay of the south aisle. The square capitals of the detached shafts on each side of this door that support a bold architrave with

a hood moulding over it, are buried in the rough acute-arched vaulting of the porch, an addition probably of the fourteenth century. The bases of these shafts are hidden by stone seats. The walls of the aisles were probably raised when the porch was built, and roofed to a pitch flatter than that of the nave, though not so flat as their present pitch, as may also be seen on the east wall of the south aisle. About 1840 the gallery which had been erected at the west end of the church was taken down, and, as a substitute, the nave was lengthened and an extra

bay added to each aisle, at the same time, probably, a clean sweep was made of all the old monuments, &c. An octagonal vestry was built out at the west end of the nave, in place of one under the gallery which was pulled down. This eccentric vestry was, in its turn, demolished about 1870, and one in no better taste added on the north of the

chancel, destroying its external features. In 1873, the church was conscientiously repaired, and an organ chamber inserted between the new vestry and the north aisle.

The first vicar of Heddon whose surname we know is John de Darlington, who exchanged the living for that of Kirkharle in 1350.

The following list [35] gives, as far as has been ascertained, the dates when his successors were appointed, and whether they resigned or died :

|

1350. John de Kirkeby.

John de Shotton, r. 1434. John Alnwick. William Baxter, r. 1492. Richard Bronndon. Christopher Cowper, d. 1542. Edward Clemetson, d. 1547. Galfrid Glenton, d. 1577. James Beake, r. 1577. Nicholas Bonnington, r. 1579. Henry Wilson, d.[36] 1580. Francis Coniers. 1584. James Hobson, d. 1613. Henry Bureil, d. 1622. Jeremiah Hollyday, d. |

1626. Thomas Taylor.

1628. Edward Say, r. 1628. William Wilson. 1642. Samuel Raine, d. 37 1662. Thomas Clarke, d. 1669. Robert Dobson, d.38 1673. Samuel Rayne, d.39 1693. Miles Birkett, d.40 1709. James Carmichael, d.41 1743. Andrew Armstrong, d. 1796. Thomas Allason, d. 1830. John Alexander Blackett, r.42 1848. John Jackson, d. 1850. Michael Heron Maxwell, d. 1873. Charles Bowlker. |

In the"Verus Valor" taken in A.D., 1288, in consequence of Pope Nicholas IV. having granted the tenths of all benefices to Edward I. for six years, the trne annual value of Heddon rectory is returned at £25 Os. 8d, that of the vicarage at £6 5s. 8d. In the "Nova Taxatio" of A.D. 1318, Heddon does not figure, doubtless owing to its having been laid waste by the Scots. Another ecclesiastical assessment, the "Nonarum Inquisitio" made in A.D., 1340, states that the tithes (valued at the same sum as in the " Verus Valor") were that year assigned to the maintenance of John de Banestre and his companions in the garrison of Berwick. By A.D. 1535 the value of the vicarage had fallen to £4 8s. Od.

35 Hed. Reg. This list, said to be taken from the books at Durham, is by no means accurate.

36 This Henry Wilson, according to Hodgson (Northd., II., ii., p. 91, n.), became vicar of Longhorsley in 1587, and did not die till 1610.

37 Samuel Raine appears to have been ejected under the Commonwealth, and Heddon Parish practically joined to Newburn, the cure of both being supplied by Mr. Thomas Dockery. Eccles. Inquests, A.D. 1650; Hodg. Northd., III., iii., Iviii. Dockery appears to have remained vicar of Heddon as late as 17th June,1662, when he officiated at a marriage. In that month Clarke first appears as vicar in the Registers ; he died 4th Jan., 1669, Hed. Reg.

38 Dobson died 27th Feb., 1671. Hed. Reg.

39 Rayne was buried in the chancel, 16th March, 1691. Hed. Reg.

40 Birkett came to Heddon, 7th August, 1691, and dying 24th May, 1709, was buried in the church on the 29th. Hed. Reg. Mr. Miles Birkett, minister of Horton, and Mrs. Jane Cowling of Bedlington, were married at Bedlington, Sept.

21, 1688. Hodgson's Northd., II., ii., p. 543.

41 Carmichael came from Ponteland 26th July, 1709 ; he died 10th June, 1743. Hed. Reg.

42 Collated to the Rectory of Wolsingham, co. Durham ; assumed the surname of Ord, in addition to Blackett, on his wife succeeding to the Whitfield estate in 1855.

36 This Henry Wilson, according to Hodgson (Northd., II., ii., p. 91, n.), became vicar of Longhorsley in 1587, and did not die till 1610.

37 Samuel Raine appears to have been ejected under the Commonwealth, and Heddon Parish practically joined to Newburn, the cure of both being supplied by Mr. Thomas Dockery. Eccles. Inquests, A.D. 1650; Hodg. Northd., III., iii., Iviii. Dockery appears to have remained vicar of Heddon as late as 17th June,1662, when he officiated at a marriage. In that month Clarke first appears as vicar in the Registers ; he died 4th Jan., 1669, Hed. Reg.

38 Dobson died 27th Feb., 1671. Hed. Reg.

39 Rayne was buried in the chancel, 16th March, 1691. Hed. Reg.

40 Birkett came to Heddon, 7th August, 1691, and dying 24th May, 1709, was buried in the church on the 29th. Hed. Reg. Mr. Miles Birkett, minister of Horton, and Mrs. Jane Cowling of Bedlington, were married at Bedlington, Sept.

21, 1688. Hodgson's Northd., II., ii., p. 543.

41 Carmichael came from Ponteland 26th July, 1709 ; he died 10th June, 1743. Hed. Reg.

42 Collated to the Rectory of Wolsingham, co. Durham ; assumed the surname of Ord, in addition to Blackett, on his wife succeeding to the Whitfield estate in 1855.

See also Appendix A for discussion of Plates.